I write dystopian fiction. It’s a cheery little pastime. I’d been working on a novel for three years about the devastation caused by a virus when a certain pathogen appeared in the world and knocked us all off track.

Image: Natalie Pedigo

March 11th, 2020 was the day we woke up to news that COVID-19 had been declared a global pandemic by the World Health Organizations (WHO). Three years on and we’re starting to recover from the impacts and to assess what went wrong, mainly with the leadership of our countries. As well as being an author, I’m a leadership consultant and the pandemic has been quite the gift in terms of material for both of those roles. I often write about military leadership, both the sort that comes with rank and the sort that comes from stepping up in a situation. The leadership we have seen during this crisis has left many questions about the ability of our leaders to ensure that all citizens are safe and secure: the absolute minimum requirement of the job.

The leadership styles of world leaders have been markedly different and that, in turn, has led to significantly different impacts on the levels of security within and across borders. Some world leaders (Jacinda Ardern, Mette Frederiksen, Sanna Marin, Angela Merkel, Tsa Ing-Wen) performed exceptionally well in the early stages of the pandemic at suppressing the rate of infection, minimizing the number of deaths, and maintaining social order in their countries. Others performed particularly badly, both at the start (Jair Bolsonaro, Boris Johnson, Vladimir Putin, Donald Trump) and throughout, and their countries face economic disaster, high death rates, and ongoing social unrest. Add in the Russian war on Ukraine, as a way of distracting from problems at home, the chaotic turnaround of Prime Ministers and Chancellors in the UK, the spiralling economic and social crises in America, and the failed zero-COVID policy in China, the complete collapse of government in Haiti, and it really does beg the question: when will the dystopian reality prompted by COVID retreat to the pages of a novel?

We need to take a look at how leaders are created in our current world to better understand how so much of the world is still struggling with a dystopian reality.

Being elected to lead a country doesn’t mean you’re a good leader. It means you know how to get elected. That involves looking good on screen, saying what people want to hear, and promising things you have never delivered before. A lot of people crave the position of high office, to lead nations and armies, but they often only have the skills to get through the interview or the contacts to put them in the frame for the top job. In some countries, that interview is an open public election, in others it’s an election by a tiny elite and, in others, it is handed down by a dynasty. Looking at the leaders in post at the start of COVID, the process of finding suitable world leaders able to keep us safe through adversity seems somewhat flawed. Democracy was no guarantee of ensuring that a chosen leader was able to create a secure environment during a global crisis. Neither was an autocracy. Rather, it is now becoming clear that the individual qualities and morals of individual leaders were what led to the most positive outcomes. And by positive outcomes, I mean fewer deaths, less social unrest, and the ability to emerge from lockdowns ready for the recovery phase of this pandemic.

Good leadership is, and always has been, open to interpretation. For some it is a case of making decisions and sticking to them, regardless of what happens. For others it is a more fluid, dynamic role, where leaders flex to the changing situation. In the worst scenarios, it is a chaotic mix of both of these. In terms of security, none of these leadership styles is adequate. In its simplest sense, leadership is the act of leading people or an organisation through a situation to ensure their safety, security, and wellbeing. But to be able to do that effectively, leaders need to be able to influence, inspire and encourage people to behave in a way which meets their objectives, whether this is making money or imposing a lockdown to prevent the spread of a virus. In this sense, leadership is the art of influencing human behaviour, to accomplish a task defined by the leader in response to an objective. Sounds easy enough if you’re already good at influencing people, but what if you’re a one-trick-pony and the only thing you can influence people to do is vote for you? What if, in fact, you’re a bad leader and you’re the worst person to be in charge in a crisis? What if you don’t genuinely care about the safety and security of your citizens as long as your own family and finances are protected?

Let’s think about that for a moment. When we choose leaders in the western world, or leaders are chosen for us, it is rarely in the heat of a global crisis. Usually, these transfers of power take place after months of campaigning and positioning. This is less the case in regions where coups and uprisings are more frequent, but leaders never come out of nowhere. They have spent years building their networks, making connections, and creating the conditions for their leadership challenge. This means that as political leaders are working their way into positions of power, their skills are not being honed or tested in response to a crisis which makes it difficult for us to know whether they will be able to lead through a crisis. The best we can do is select our leaders on the basis that they should either have intrinsic attitudes, values, and behaviours that will enable them to act wisely in a crisis, or that they should have proven skills in another arena that demonstrates they have good judgement when all hell is breaking loose. We need people who have experienced chaos and created calm.

To be able to do this, leaders need a combination of three things. First, the leader should know their responsibilities and be ready and willing to lead, even if that means they won’t be popular. Second, if the leader isn’t the best person for the situation they need to step back without hesitation and support the person who is best suited to lead through the situation. Third, if a leader doesn’t have the skills to lead, or to contribute to the team who are best placed to deal with the problem, they should stand aside entirely. The problem with most leaders is that they don’t have the self-awareness and humility to know when they’re making things worse and when they should step down.

As well as knowing when not to lead, leaders also need to be able to give unpopular messages and still bring people along with them on a difficult journey. Promising cake today and cake tomorrow won’t keep the peace when people realise there is never going to be any cake because you haven’t secured any of the ingredients or you’ve sold them to your neighbours for a nice profit. The most effective global leaders have shone in this crisis because they have been able to demonstrate and communicate compassion, fairness, good judgement, and clarity in their decisions. At the same time, they have been truthful about what they know and don’t know about the situation without causing panic. As a result, citizens trusted them to act in their best interests and have been willing to comply with inconvenient measures, some of which have meant putting the needs of others before their own needs and wants. Excellent judgement, both in the hard decisions and in the way these are communicated, has underpinned much of this trust. In the countries with poor outcomes, the social contract between state and people is broken. Leaders have failed to provide a consistent form of leadership that offers an alternative to the very logical individual actions made in the absence of effective government.

If so many global leaders are failing to perform in a crisis, then what about business leaders? Are they showing more leadership skills or are they making the same mistakes? Seniority or your position within the hierarchy of a corporation might give you the title of leader but being a senior executive is, well, just that: a senior executive. It doesn’t make you a great leader, especially not in an unprecedented situation like a pandemic and subsequent global recession or the unfurling climate catastrophe or the collapse of government in Haiti or the destruction of human rights in Afghanistan. There are no guarantees that organisations have recruited people with the right leadership skills for the crises we now find ourselves facing. To some degree, that’s not unreasonable as we can’t always be expecting the worst to happen. But if we choose leaders for more than their ability to agree with us or to look good on TV we may be able to weather future crises more readily.

So, what do world leaders have to learn from each other and from the successes of business leaders?

Watching the response of individuals, communities, and businesses has been reassuring. Where there have been failures in neo-liberal and libertarian governments, focused on being elected rather than making unpopular decisions, people have developed their own approaches to ‘leading from within’ to ensure the security of their people, resources and organisation. This approach prioritizes people over processes or profits and demonstrates visibility in leadership decisions and actions. It requires mature, confident, and competent leadership that is fair and consistent when challenged or threatened. Leading from within means leaders must truly lead from within, regulating their own emotions, desires, and behaviours, before attempting to lead others.

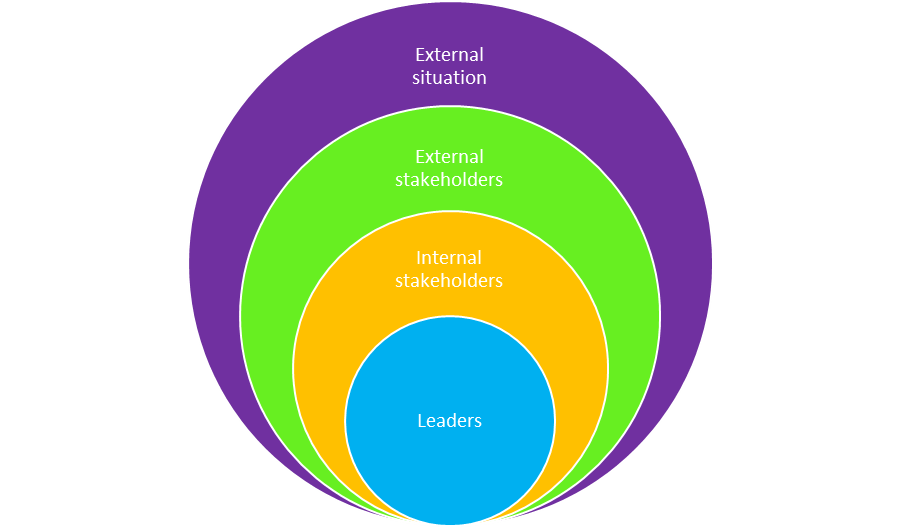

The diagram below shows how leading from within offers a model of influence more suited to preparing for and leading through a crisis than the ones we have seen in many governments. Leaders sit at the core of the organisation, bearing the weight of the competing influences on the organisation. At the same time, they radiate their decisions up and out, rather than imposing decisions and behaviours from above.

This type of leadership is one more akin to the military as it requires trust to be established throughout the organisation so that decisions are implemented swiftly and without dissent when a crisis emerges. Loyalty to a common cause and loyalty to colleagues is also part of this model. Again, familiar military concepts. A leader who leads from within is able to create the conditions for this model to operate both in a crisis and as part of business as usual. Ultimately, the weight of all decisions is at the base of this model, resting with the leader. The positive influence that moves through the organisation, by keeping internal stakeholders close and ensuring transparency in decision-making, encourages a culture of trust and a sense of security. The leader in this model is able to create calm from chaos because they have already established the conditions needed for success in a crisis.

As is seen in so many conflicts, peace is dependent on structure and certainty. Where governments fail to reassure and secure their citizens, those citizens will self-organise and if this is for basic survival it is likely to be enacted against a backdrop of social or civil unrest. In the West, we have had the luxury of wealth and relatively good infrastructures to carry us through the worst of the pandemic. This has afforded many people the chance to discover creative ways of reconnecting with each other and doing business. Online volunteering groups, individual fundraising, and public gestures to recognise those who are showing courage and initiative (such as first responders), happened quickly and organically. While governments were busy working out what suited their political goals, people got on with the important business of surviving. In other less economically secure nations, organising an online quiz night was not an option when essential services and supplies weren’t even available. Experiences of the pandemic vary widely, depending on the leadership in place at the outbreak of the virus and the existing national resources. This is nothing new, but what is new is our ability to scrutinise the effectiveness of different leaders and leaderships styles. COVID gave us a unique ability to compare and contrast the outcomes of every nation at a given point in history. It seems that the countries that fared best at the beginning of the pandemic had leaders who were trusted by their communities, communicated well, and made tough decisions to protect their national borders and to enforce lockdowns even when it made them unpopular.

But, somehow, things get done in a crisis, even when leadership is weak. We’ve all seen it and all been surprised by it when, in the face of what seem like terrible leadership decisions, we muddle through. That’s because leadership from within will happen intuitively when the people in charge fail to lead effectively. People will step into the void left by poor leaders and will make decisions to suit their own moral compass and situation. Unfortunately, this often covers up leadership failures, particularly in a crisis, and can lead to distortions in what is seen as success. Poor leaders will take the credit for what goes right in a crisis and will distance themselves from the mistakes. World leaders who have insisted on leaving decisions to the common sense of their citizens, have fundamentally failed in their role as a leader. Decisions such as self-isolation, social distancing, when to close borders, track and trace policies, and purchase of medical grade PPE for health workers cannot be made by individuals. This is why we have leaders: to make difficult decisions on our behalf, manage scarce resources, and to make best use of our taxes because they have oversight of the situation. Leaders who are more focused on their personal popularity with the electorate, leading from on high and perpetuating self-interested behaviours have witnessed increasing social unrest, civil disobedience, and industrial action. The more isolated they have made themselves, the less able they are to maintain peace and harmony in their populous.

Leadership styles are not just theoretical. They matter in a crisis because they will make or break a business or a country. What we have seen is that leaders who lead from within, by being closer to their people and by understanding the reality of the situation, have been more effective at all stages of the pandemic. What remains to be seen is whether this style will be equally valid in a world experiencing economic instability, rapid technological advances, and the impending catastrophe of climate change. The likelihood of maintaining peace in the future, within nations and across borders, is looking increasingly challenging in a world where crises are more frequent and more global.

Bev Morris